I’m picky about restaurants: working in the specialty food business for thirty years exposes you to some of the tastiest (and sometimes weirdest) ingredients in the world. It’s hard for me to pay good money for uninteresting food and poor execution.

I’ve been known to research the food scene at my destination prior to traveling. It certainly doesn’t preclude random discoveries that often reveal delicious options but I usually have a list of old favorites or new go-to places in case nothing exciting turns up. No Michelin-starred establishments, more like “little holes in the wall” that prepare pristine sushi, a superlative cheesy-corny quesadilla, the lightest fish and chips, or a perfectly cooked angler steak with shallot sauce.

Then there is air travel, airline food, and airport restaurants. Ugh.

My default flight from Paris to San Francisco requires me to check in at 7 am at CDG1. I have two options. The evening before departure, I can spend the night in Paris proper and enjoy a superlative dinner just about anywhere; but that also means getting up at some ungodly hour to reach the airport on time, hoping to avoid rush hour traffic or praying the RER trains are not affected by the all-too-frequent strikes. Or, I can minimize my morning stress and stay at an airport hotel: it seriously reduces my dining choices but it makes me a more pleasant traveler the next day.

Over the years I’ve tried a few hotels around the airport but there is one particular restaurant that I particularly favor: the Novotel Café that is steps away from the RER/CDGVAL transportation hub. I would describe it as a modern brasserie where you can order a perfectly seared entrecôte, a risotto with cèpes mushrooms, or a runny chocolate lava cake. The wait staff is impeccably dressed in white shirts and black slacks or skirts. It’s not an airport cafeteria, nor a restauration rapide joint: the setting is not too casual and they aim to provide a finer dining experience than what you would expect at an airport.

During my last visit, my table was located by the glass partition that separates the dining room from a lush bamboo garden: it’s a green haven that makes you temporarily forget the ever-present concrete and uninspiring architecture of the train station (if you’ve been there, you know what I’m talking about.) It was close to 8 pm. I was by myself this time, sipping a glass of Rosé and enjoying a delicious plate of salmon sashimi when my eye caught an unusual reflection in the glass wall: an explosion of flowers. I turned my head and noticed that two 40ish women were now sitting ten feet in front of me. Both were wearing mid-calf dresses that seem to be cut from the same pattern, the same black fabric, and the same floral print, albeit red for one and green for the other. Big hair and make-up. Immaculate white tennis shoes. They shared a bottle of Les Jolies Filles Côtes-de-Provence Rosé. They spoke in French. Obviously, two BFF gearing up for a trip to… Barcelona? Berlin? Marrakech?

I started to scan the room, observing my fellow diners, trying to figure out their respective destinations. The gentleman by the wall to my right was easy to peg: 50ish, jeans, white shirt, navy blue blazer hanging on the back of his chair, reading the latest Haruki Murakami’s novel. Tokyo-bound for sure. Further back, three middle-aged men, all in pale blue button-down shirts and V-neck sweaters; animated conversation; probably discussing the deal they would iron out in New York or Boston; probably flying Business class or hoping for an upgrade. The older couple a few tables in front of me was already in the dining room when I arrived. They had ordered the three-course meal with a bottle of wine and Champagne. They lingered, squeezing and enjoying every last minute of their anniversary vacation in Paris (?) before returning home to the US. As I was finishing my herbal tea, a middle-aged couple arrived; he wore a Hawaii surfing t-shirt; she asked for green vegetables instead of potatoes; their English sounded sans accent to my Californian ear. I was pretty sure they would be boarding my flight to San Francisco the next day.

Faces, places. People-watching is almost a national sport in French cafés. Perhaps they too were guessing the destination printed on my boarding pass.

Vocabulary

L’entrecôte (f): rib-eye steak

Le cèpe: porcini

La restauration rapide: fast-food

Sans accent: without accent

BOUILLON CHARTIER

Confession time: I love Parisian brasseries. Not so much because of the food they serve: although I have been pleasantly surprised at times, dishes can be a bit pedestrian. But those venerable restaurants exude history and personality. To have a meal in a traditional brasserie is to be transported in time: Belle Epoque, Art Nouveau, Art Deco… pick your favorite era. I often dine alone when I am traveling and I refuse to surrender to room service: a brasserie is always warm and welcoming of solo diners. There is an element of predictability in the menu: you can be pretty sure the steak-frites and choucroute garnie will be decent, if not very enjoyable. Service is fast and efficient: watching the waiters clad in in their traditional uniform of black pants, white shirts, black vests and white aprons is akin to attending a well-rehearsed ballet at Opéra Garnier. And, of course, the décor provides endless amazement, inspiration, and surprises: I captured the perfect shot for the cover of my book while dining at Brasserie Julien!

From 7 rue du Faubourg Montmartre, enter the stone courtyard to reach the revolving door entrance to Bouillon Chartier.

Many brasseries offer service continu, which means that you can pretty much order coffee, wine, or food from 7 am to midnight. The “fancier” ones may not offer breakfast but will stay open quite late, so you can still enjoy a leisurely dinner after the theater. On the other hand, if you landed in Paris at 10 am after a very long flight and you are fighting jet lag, you probably just want to get a decent meal on the early side.

Old-fashioned wood chairs and tables, basic tabletop and glassware, real fabric tablecloth topped with disposable white paper.

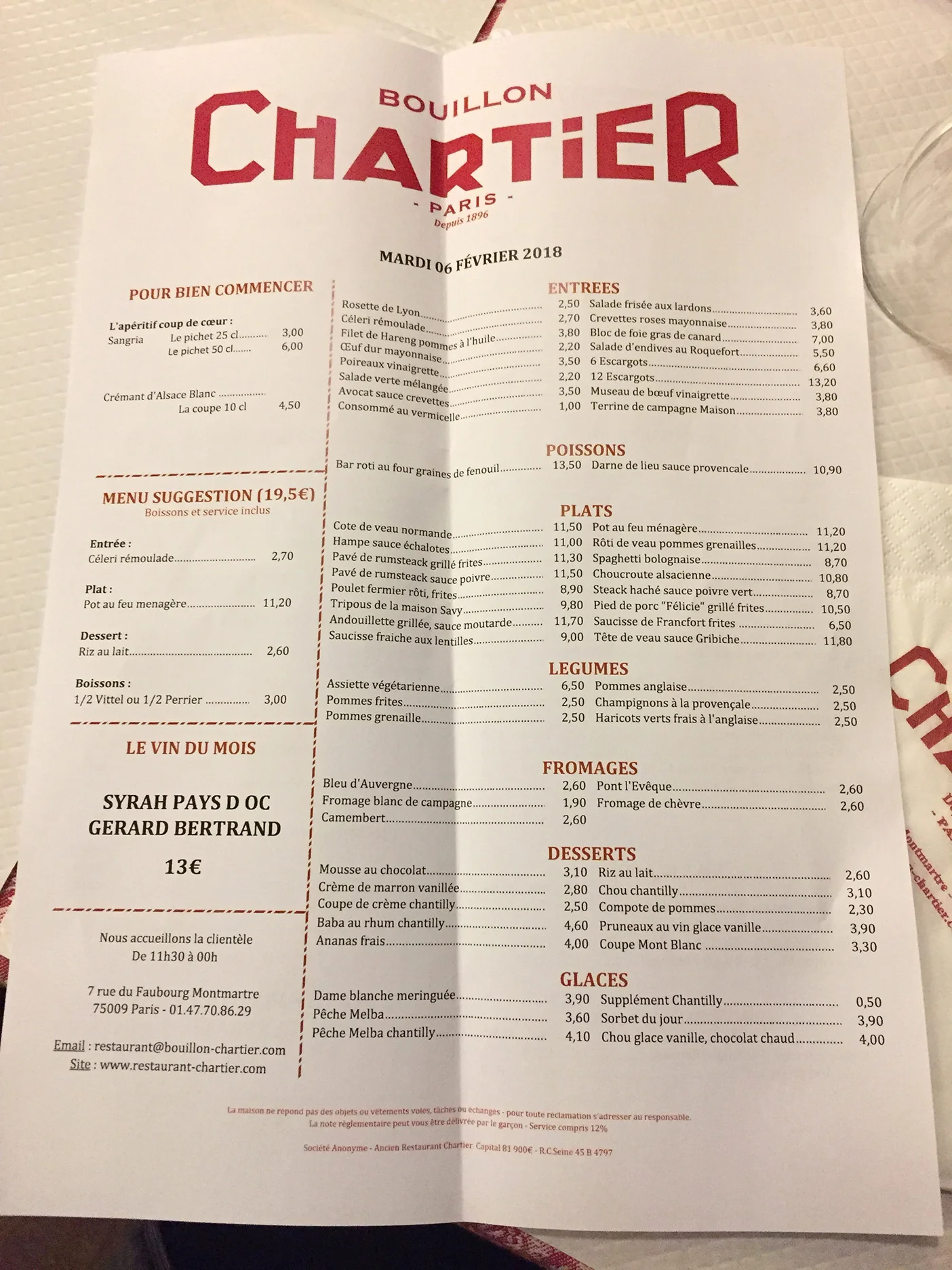

The evening of our arrival in Paris last month, Rick and I dined at Chartier. They don’t take reservations but they serve food non-stop from 11:30 am to midnight. We showed up at 6:30 pm (how un-French of us) and were seated immediately. One doesn’t go to Chartier for a gastronomic experience: since its very beginnings in 1896, the goal of Bouillon Chartier has been to provide a decent meal at a reasonable price and they continue to deliver on that promise. One could even argue that bouillon was the original fast –and cheap– food. Check out the menu: where else in Paris can you get a bowl of soup for 1 euro?

Consommé au vermicelle (broth with vermicelli) for 1 euro! A bottle of red wine for 13 euros!

A hundred years ago, the typical Chartier customer was a Parisian worker; on that night last February, half of the dining room seemed to be filled with tourists. I didn’t mind. The food was satisfying and inexpensive. The atmosphere was lively and unpretentious. The Belle Epoque décor was simple yet gorgeous. Good times. I’ll let the photos speak for themselves…

The dining room: chandeliers, mirrors, and painting by Germont.

In the old days, "regulars" would keep their cloth napkins in their own numbered drawers. Not quite sure about the numbering logic there...

We were seated next to a bank of napkin drawers. I was very tempted to open one of them. Should have... Brass racks above the tables allow patrons to stow purses and coats.

Yes, there is a mezzanine! Brasserie waiters always look so sharp in their black and white uniforms.

Rick ordered escargots for his first course but I don't believe he used the snail tongs. Maybe he was afraid of flinging the shells across the dining room like Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman?

My frisée aux lardons was copious and satisfying.

L'addition, s'il vous plaît! Scribbled on the paper tablecloth. Two first courses, two mains, one shared dessert, wine, and coffee for 42.20 euros. That's hard to beat in Paris!

On the way out, there is a gift shop where you can purchase mugs, dishtowels, playing cards. magnets, or a "Cuvée Chartier" bottle of wine.

Does this look like the lines at Disneyland? When we left around 8:30 pm, there were a lot of people waiting to get in. Chartier doesn't take reservations and it's a popular place: go early or go late. Or just wait: worthwhile experience, if you ask me.

Vocabulary

Le steak-frites: steak and French fries

La choucroute garnie: sauerkraut garnished with an assortment of pig meat products

Le service continu: non-stop service

Le bouillon: broth

L'addition: the ticket

S'il vous plaît: please

THANKSGIVING, FRENCH-STYLE

Like all French expats I’ve been asked, more than once, how we celebrate Thanksgiving in France. Well, we don’t: I suppose we really want to save our appetite for Christmas. Just kidding: the French would never turn down an opportunity to party and eat good food but I’m certain we would approach it differently.

Attending my first Thanksgiving dinner was an eye-opener. After watching my mother-in-law and my sisters-in-law frantically shop and cook for three days, I was dismayed to see how quickly the meal was over: everything –except for dessert– was set on the table all at once. All dishes, hot and cold, savory and sweet, were served together and mingled on the plate. Everything looked fabulous but this French girl was a bit, uh, overwhelmed by the pacing of the meal. I think the guys in the room gave up on me and retreated to watch football while I was still working on the cranberry ambrosia.

When Rick and I moved to our current home in 1991, the floor plan allowed us to set up a separate salle à manger, one that would accommodate holiday dinners with the whole family. We were finally able to use the leaves on his grandparents’ dining room table and have 12-14 people over for dinner. I quickly volunteered to host Thanksgiving that year. Of course, it was going to be my own take on the beloved American celebration.

I wanted the meal to last more than half an hour so I decided to serve it in courses. First, une soupe. Pause. Then, une salade composée. Pause. Then, le plat de résistance. That year, it would not be a turkey: I was making confit de canard and pommes de terre sarladaises thanks to a business connection who supplied me with 10 lbs of fresh yellow chanterelles. Green beans with garlic sautéed in duck fat. And the cranberry ambrosia that Debbie makes (I love it, it’s like dessert to me.) Pause. Then, pumpkin pies and an apple pie that Debbie baked especially for me because she knows that, to this day, I will not eat pumpkin pie. I do believe that most French are genetically programmed to reject la tarte au potiron, le beurre de cacahuète and la bière de racine.

I was pretty happy with myself and thought I had conquered a seminal American holiday: my convives enjoyed their meal and, although it did not end in song and dance like most French celebrations do, we actually spent a couple of hours sitting and conversing at the dining room table, somewhat of a record from what I had previously observed.

Ten months later, the cruel reality hit: although my Thanksgiving dinner had been enjoyed by all, Kim pointed out that it didn’t really feel like Thanksgiving because: no turkey, not dressing, no leftovers. I realized that holidays are not just about the food itself but also about rituals.

For my 1992 edition of Thanksgiving, I relented and roasted a turkey. It was epic. And worthy of another post one year from now. In the meantime, I’ll share with you what the French love to make with a nice pumpkin.

Vocabulary

La salle à manger: dining room

La soupe: soup

La salade composée: mixed salad

Le plat de résistance: main course

Le confit de canard: duck confit

Les pommes de terre sarladaises: potatoes sautéed in duck fat

La tarte au potiron: pumpkin pie

Le beurre de cacahuète: peanut butter

La bière de racine: root beer

Les convives: dinner guests

Pumpkin soup

Soupe au potiron

2 tbsp olive oil

5 large shallots, chopped

2 large cloves of garlic, minced

3 lbs pumpkin flesh, peeled, seeded and cut into 1-inch cubes

1/2 lb russet potatoes, cut into 1-inch cubes

1 tbsp sea salt

Black pepper

4 1/2 cups of chicken stock

1/2 cup heavy whipping cream

1 Tbsp fresh parsley or chives, chopped

In a large pot, heat the oil over medium heat. Add the shallots and garlic; cook for 5 minutes, stirring occasionally until the shallots are soft and translucent. Add the pumpkin, potatoes, salt and freshly ground pepper. Cover and cook over medium heat for 10 minutes. Pour in the chicken stock and simmer for 45 minutes until the pumpkin is tender. Puree the soup in batches until smooth. Return to the pot, add the whipping cream and the parsley and stir. Check seasoning and serve immediately.

In full confrérie attire to serve cassoulet

CASSOULET

I confess that I didn’t make cassoulet from scratch until I moved to the United States. Premièrement, my mother was a very competent cook so there was no compelling reason to take over her kitchen. Deuxièmement, cassoulet was readily available in France; even the inexpensive canned versions from the grocery store could satisfy my student friends. Troisièmement, let’s face it: cassoulet is a labor-intensive dish to make. Once in California, I had to do without Mom’s cooking or French-food-in-a-can and, when sufficiently motivated, I would hunt for the necessary ingredients such as Tarbais beans, confit de canard, duck fat, and Toulouse-style sausage. Unconsciously, I may have started my mail-order business just to eliminate the hunting part.

Cassoulet started out as peasant food, a ragout of fava beans that included whatever leftover meat was at hand. White beans were not introduced in Europe until the 16th century but have become the foundation of the dish. France being France, there are arguments about which beans should be used (lingots, cocos, tarbais?) and which meats should (or should not) be added: confit (duck or goose?), pork, lamb, perdrix? And how many times to break the crust? Castelnaudary, Carcassonne, and Toulouse are the three cities claiming they have the “right” recipe. In reality, there are as many variations as there are cooks and, in my mind, it’s a good thing.

Since I was in Carcassonne a month ago, it would have been a dereliction of duty to leave town without sampling some cassoulet. So, I’m going to recommend L’Auberge des Lices in the Cité not just because the cassoulet was very good, not just because the server wore his confrèrie garment, but also because the restaurant was filled with locals who spoke with their lovely Occitan accent: if they grew up on cassoulet, they must know where to enjoy a good one.

Vocabulary

Premièrement: firstly

Deuxièmement: secondly

Troisièmement: thirdly

Le confit de canard: duck confit

Le haricot tarbais: a large white bean from the Tarbes area where a bean and a corn kennel are planted together; the corn stalk serves as a stake for the climbing bean plant.

La perdrix: partridge

La confrèrie: a guild that celebrates a particular product

L'Occitan: an old language of southwestern France

Baked in and served out of its earthenware dish

Cassoulet with duck confit

Cassoulet au confit de canard

4 cups Tarbais beans

2 carrots, peeled and cut in 1/2” slices

½ onion, studded with one whole clove

3 oz slab bacon

1 bouquet garni (thyme, bay leaf, parsley)

2 tbsp duck fat

6 legs of duck confit

1 lb Toulouse sausage

½ onion, chopped

2 tbsp flour

2 tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and cubed

2 cloves of garlic, crushed

1 cup dry breadcrumbs

Soak the beans overnight in cold water to cover. Rinse and drain the beans. Put them in a large cooking pot and cover with cold water. Add the carrots, clove-studded onion, bacon slab and bouquet garni. Bring to a boil, then lower the heat and simmer for 1 1/2 hours. Preheat the oven to 350ºF. While the beans are simmering, melt the duck fat in a Dutch oven; brown the duck confit and the sausages on all sides. Add the chopped onion and cook until soft but not colored. Sprinkle with the flour and stir. Add the tomatoes, the crushed garlic and half a cup of water. Simmer for 10 minutes on the stove. Transfer the confit and sausages to a bowl. When the beans are almost cooked (tender but offering a slight resistance), drain and add the beans cooking liquid to the reserved sauce in the Dutch oven. Discard the bouquet garni. Remove the slab bacon, cut into dice and set aside. Cover the bottom of a large baking dish with a layer of beans. Add the sausages and confit and about 1 cup of the reserved liquid. Cover with another layer of beans and top with the pieces of bacon and more liquid. Sprinkle with breadcrumbs and drizzle with a little extra duck fat. Bake for 1 hour, or until the breadcrumbs are lightly colored, and serve in the baking dish.

Tarbais beans, duck fat, duck confit, and Toulouse sausages are available from Joie de Vivre.

LES CHAMPIGNONS

Fall might be my favorite season in southwestern France, perhaps because I’m still discovering the sights and smells at that season. Although I spent a lot of time at my grandparents’ farm while growing up, I was never there between la rentrée and Christmas: I usually left early September to get ready for school in Paris. My biggest regret is to have never experienced les vendanges: after tending to the vineyard throughout the Summer, I would have loved to be there when all our neighbors came to help harvest and stomp the grapes.

These are pretty but I don't eat them...

By chance, a couple of trade shows take place in Paris in September and in October: in the past few years, I’ve had a few opportunities to catch the train and meet with the family for a few days. The vineyard is gone but we still harvest walnuts, chestnuts, apples, and quinces. And, if the weather and the moon cooperate, there might also be mushrooms. I got an early education in mycology under the guidance of my dad and my grandfather who were both avid foragers. I quickly learned to recognize the good, the bad, and the ugly but if you’re not sure what to pick, you can always take your mushrooms to the local pharmacy and they will tell you what to keep and what to discard. Try doing that at CVS!

Morels!

In spring, we searched for morilles. They’re small and hollowed: it takes a lot of these to make a pound! My largest morel find actually happened in the US. I was working in Chico at that time and renting a little condo with a small backyard that had been dressed with a layer of bark from the Sierra. One evening in March, I stepped outside and noticed something that looked like a small sponge. Upon closer examination, I was sure it was a morel. I was shocked! As I bent over to pick it up, I realized the whole backyard was teeming with morels! I had never seen that many of them in my whole life. I gathered close to two pounds of fungi within minutes. I called my travel agent (she lived in the same complex, a few units down from me) and asked her to take a look at her backyard: could she see mushrooms there as well? Yes! I told her they were some of the most sought-after mushrooms on earth and shared my favorite recipe. Chris was absolutely horrified that I would be eating mushrooms that were not store-bought. She actually called me at the office the next morning to make sure I was still vivante.

Morels come in different colors: blond, gray, and dark brown. Different shapes, too.

In summer, we usually found cèpes: those are large and heavy. If you know where to look, you can pick up several pounds very quickly. But my all-time favorite mushroom is the girolle: I love its very distinctive texture and its nutty flavor. After walking in the woods for a couple of hours, always accompanied by grandfather’s Brittany spaniel, I usually came home with three to four pounds of girolles that we would immediately prepare for lunch. Grandma simply sautéed them in duck fat, along with scalloped potatoes, seasoned with a lot of garlic and fresh parsley. The aroma would fill the whole house (well, it’s a small house…) To this day, it remains one of my very favorite dishes.

Vocabulary

La rentrée: back-to-school

Les vendanges: the wine harvest

La morille: morel

Vivant(e): alive

La girolle: golden chanterelle

Le cèpe: porcini

Girolles and potatoes sautéed in duck fat, just like in Sarlat!

Pommes de terre Sarladaises

Potatoes sarladaises

3 tbsp duck fat

½ lb wild mushrooms (chanterelles, porcini…)

1.5 lbs potatoes

Salt and pepper

5 cloves of garlic, chopped

Fresh parsley, chopped

Clean and slice the mushrooms. Sauté in 1 tbsp of duck fat for 5 minutes (until they’ve released their water) and reserve. Peel, scallop and rinse the potatoes. Dry them thoroughly. In a heavy sauté pan on medium-high, heat the remaining duck fat. When the fat is hot, throw the potatoes into the pan and cook for 5-10 minutes until golden. Gently flip the potatoes over with a wide spatula and cook another 10 minutes. Add reserved mushrooms. Add garlic, parsley, salt, and pepper to taste. Mix together and cook 5 more minutes. Serve immediately.

If wild mushrooms are not available, you may use crimini or Portobello. But you MUST cook them and the potatoes in duck fat. Potatoes will be crispy but tender inside. Yum!

Duck fat can be purchased at frenchselections.com

TO MARKET, TO MARKET

France has not been immune to the transformation of the retail scene: big box stores and supermarkets ushered the sad decline of old-fashioned, family-owned specialty shops. But one tradition is holding steady: the weekly open-air markets. I simply love them, especially those in the countryside where just about everything offered is farmed or raised locally.

When my sister and her family moved to Grenade-sur-Garonne, our Saturday morning routine included a long visit to la halle, the medieval covered structure in the center of town. Farmers and vendors display their bounty under the tile roof and along the adjacent streets: mounds of tasty saucissons (made from a dozen different meats), regiments of disks and pyramids of chèvres perfectly lined up in their refrigerated cases, baskets of brown eggs with an occasional feather stuck to their shell, colorful bunches of cut flowers soaking in tall galvanized buckets, and produce galore. As a little game, I would ask my toddler nephews to identify and name every single légume we saw while filling our cabas. Afterwards, we’d grab an outdoor table at one of the cafés lining up the square and order un Ricard or un demi for the adults, une orangeade avec une paille for the younger set.

La halle de Grenade is quite remarkable: with its thirty-six octagonal brick pillars and massive oak carpentry, it was specifically built in the 13th century to hold a weekly market. Weights and measures were kept in one of the upstairs loges; another one was used as a workplace for the judge, the mayor, or the notaire. Pigeons still roost there.

In addition to the market, la halle is also the site of special events such as the famous “Sausage Fair” organized by the Confrèrie Gourmande et Joviale de la Saucisse de Grenade. Pageantry is served, along with endless arguments about the merits of the local sausage versus the one made in Toulouse, a mere 15 miles away…

Vocabulary

La halle: covered market

Le saucisson: dry cured sausage (like salami)

Le chèvre: goat cheese

Le légume: vegetable

Le cabas: old-fashioned grocery bag

Le Ricard: brand of a pastis drink

Le demi: draft beer

L’orangeade: water with orange syrup

Avec une paille: with a straw

Le notaire: a public officer who records contracts, property inheritance, wills and other documents in every area of law

BISTRO CHAIRS

Everybody dreams of taking a break, sitting en terrace, and watching the world go by while sipping une noisette, a glass of rosé, or a Perrier rondelle. And people actually do that in Paris: tourists, of course, but also the locals. Students gather in bistros year around as a more lively alternative to the library. Female friends meet for tea and a pastry in the afternoon. Others enjoy cocktails at Happy Hour. Some catch a film and finish off the night with moules frites and Belgian beer. Bistros are no mere watering holes: they also perform a social function.

And everybody sits in the ubiquitous rattan bistro chairs, without paying much attention to them. For more than 100 years, they’ve been part of the Parisian urban scenery as much as the Guimard métro entrances, the newspaper kiosks, and the Morris columns. All these chairs are made by two manufacturers: Maison Drucker (est. in 1885) and Maison Gatti (est. in 1920). You will occasionally find some cheap Chinese imitations but the authentic, made-in-France models will have a small brass plate attached to the frame: check it out next time you rest your tired derrière!

Although there are only two makers and they both use the same materials, the variations are almost infinite: different styles of frames, different patterns and dozens of colors for the seats and backs. The rattan is cut, steamed, bent, and assembled by hand. Rilsan (which comes from the castor oil plant) is dyed by injection and woven by skilled artisans: its color never fades even when exposed to the sun and it will sustain wide variations in temperatures without cracking. Although many famous cafés special order their “signature” chairs, there are enough choices for each neighborhood bistro to create its own look.

The popularity of these chairs doesn’t wane: they’re elegant, comfortable, light, and durable. And they stack so easily! Closing shop after a busy day is (almost) a breeze. Even Mr. Bear approves… Grab a chair and make a new friend.

Vocabulary

En terrace: on the terrace (where drinks will cost you more…)

Une noisette: an espresso shot with a touch of milk (lit. a hazelnut)

Perrier rondelle: a glass of Perrier with a slice of lemon

Moules frites: mussels and French fries

Le derrière: you know what that means; yes, you, do.

MICHELLE'S CHOCOLATE MAYONNAISE CAKE

Truth be told: I didn’t start cooking until my twenties. I had plenty of opportunities to learn from the best: my mother and grandmothers were all excellent, intuitive, confident cuisinières who whipped up two meals a day without the aid of any book. I just wasn’t interested. My desire to know how to cook developed quite suddenly, after my second trip to California, but I’ll save that story for another time.

Not knowing my way in the kitchen didn’t mean that food was unimportant to me. After all, it is hard to grow up in France and think about food as mere sustenance. I had definite ideas about what I liked and which ingredients usually combined in a tasty way. During my trips to England, Italy, and Germany, I also had the pleasure (or displeasure) to challenge my taste buds with the unfamiliar: beans on toast, grilled octopus, or cheese with music (look it up…)

In general, I was not surprised or offended by American food when I came over to the US. The notable exception was desserts: some of the ingredients just made me cringe. Mincemeat pie? Really? I never got used to that one. I had heard of carrot cake and it didn’t sound appealing. Luckily the first one I was served was baked by Debbie, my sister-in-law-to-be: her recipe is simply the best and it has become one of my favorite cakes. I also tried zucchini bread made by Terri (my other sister-in-law-to-be) and it was quite enjoyable. After a while, my mind finally accepted the notion of incorporating vegetables into baked goods.

At some point, Rick raved about Michelle’s chocolate mayonnaise cake and it just sounded gross to me. I had watched my dad make mayonnaise from scratch too many times to ignore that it contained black pepper, vinegar and –gasp– Dijon mustard. Quelle horreur! By now you probably know where this story is heading. Yes, Frank and Michelle invited us over for dinner. Yes, a chocolate cake was served. And yes, it was absolutely delicious. I asked for another slice and for the recipe. I learned a few lessons that night. First, one should always approach new foods with an open mind. Second, break down a preparation into its components: after all, mayonnaise is mostly composed of eggs and oil, the “usual suspects” in baked goods. Third, read the labels: American mayonnaise is made sans moutarde…

Michelle died of cancer while I was in France last month. Her Facebook page was flooded with tributes and memories. Her granddaughter Sara brought up the chocolate mayonnaise cake: judging from friends and family’s reactions, I think it’s safe to call it her signature dessert. Last Saturday I felt a sudden urge to bake (trust me: it’s not a normal state for me.) Locating the recipe was a cinch: I knew I would find it in my very first American recipe folder, the one I started thirty-five years ago. So, I baked my cake and cried. Losing a long time friend is hard but thirty-five years of shared meals and laughs and songs sparked many of those moments parfaits I love so much. Her famous chocolate mayonnaise cake is only one of them; the oldest one.

Vocabulary

La cuisinière: (female) cook; also, the stove

Quelle horreur: how horrible

Sans moutarde: without mustard

Michelle’s Chocolate Mayonnaise Cake

1 box Duncan Hines Devils Food cake mix

4 oz package instant chocolate pudding

4 eggs

¼ cup mayonnaise

½ pint sour cream

1 tbsp almond extract

½ cup vegetable oil

½ cup water

6 oz chocolate chips

1 cup almond slivers

Butter and cocoa powder for the pan

Preheat oven to 350º. In a large bowl, combine cake mix and chocolate pudding. In another bowl, combine eggs, mayonnaise, sour cream, almond extract, oil, and water. Add wet ingredients to dry ingredients and beat until smooth. Fold in chocolate chips and almond slivers. Butter a bundt cake pan and dust with some cocoa powder. Bake for about 55 minutes.

Sylvaine’s tip: I like to serve it with a raspberry coulis and a dollop of whipped cream.

I did not take the photo included in this post but I do not know whom to credit (if Frank lets me know, I'll update.) It's one of my favorites; it was used for an open house at their design/art gallery.

P'TIT DEJ'

Rumor has it that the French don’t “do breakfast.” According to another rumor, we pig out on croissants all the time. So, what constitutes a typical petit déjeuner français? It’s true that most French people have a light breakfast at home before heading out to school or to work: a glass of juice, a bowl of café au lait, a tartine or a couple of biscottes with butter and jam; that’s about it. Habits have changed somewhat: a cup of yogurt or some cold cereal might also make an appearance. Croissants are weekend treats, unless… I confess to being a serial croissant eater when I am in France: good ones are impossible to find in Modesto so I make up for it when I find myself in Paris. It’s quite special to start the day at a neighborhood café and watch the regulars interact with the servers while sipping a nice cup of tea or coffee in which I blissfully dunk a long slice of crispy baguette smeared with Brittany butter (the kind with salt crystals); and a perfect croissant, because every day feels like Sunday when I am in Paris…

Vocabulary

Le P'tit dej': short (and familiar) for le petit déjeuner

Le petit déjeuner français: French breakfast

Le café au lait: coffee mixed with milk (usually in about equal proportions)

La tartine: a slice of bread topped with other ingredients

La biscotte: a store-bought bread product similar to Melba toast

PAULA WOLFERT

After moving to the USA in the early 80s, I had a standing Saturday rendez-vous with PBS and their lineup of cooking shows. There were only a handful of celebrity chefs back then: Julia, Jacques, and Justin who always sipped some of the wine his recipe called for.

I had never heard of Paula Wolfert until I noticed one of her books at my –now defunct– favorite bookstore: The Cooking of Southwest France. The 1984 soft cover edition didn’t have any mouth-watering color photos but I hardly needed them: I was in familiar territory. The list of recipes immediately transported me back to my grandmother’s kitchen where she would cook the mique in the fireplace, simmer her civet de lapin on one of her two gas burners, or bake a clafoutis in a tiny windowless oven. Reading Paula’s anecdotes and notes to the cook, I could have sworn that she had actually met my grandma, helped her pluck a chicken and shared a glass of ratafia while chatting about peasant life in the Quercy. I bought the book.

Paula called my office twenty years later. I recognized her name as soon as she introduced herself. She had just completed the revised edition of her book. Before listing Joie de Vivre as a resource for meats and grocery items, she wanted to talk to a “real” person and make sure the company would be around for a while… We had a very pleasant conversation and I felt like I was talking to an old friend. A few months afterward, a fresh copy of the completely updated Cooking of Southwest France showed up in the mail. Before I had a chance to shelf the new hardcover tome next to my original copy, Emma (long hair dachshund #2) managed to gnaw on the bottom right corner of the book; perhaps to indicate interest or register approval…

I never met Paula in person but kept aware of her subsequent publications: the foods of Morocco, Spain, and the Mediterranean received the same in-depth treatment as Southwest France. I eventually followed her on Facebook, shortly after she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Far from hiding her illness, she has embarked on a new adventure, exploring the relationship between food and memory; and Emily Kaiser Thelin, her former editor at Food and Wine, just published a biography (Unforgettable: The Bold Flavors of Paula Wolfert’s Renegade Life) interwoven with fifty quintessential recipes. In case you’re wondering, her famous Toulouse Cassoulet recipe is included: it’s widely considered the gold standard. It sounds like a fascinating read and I’m pretty sure I’ll pick up a copy. I just need to make sure that Lily (long hair dachshund #3) doesn’t chew on it…

Vocabulary

La mique: a big dumpling cooked in broth and vegetables

Le civet de lapin: rabbit stew in red wine

Le clafoutis: a custardy cake, usually filled with cherries

Le ratafia: a sweet aperitif made with non-fermented grape juice and brandy. It can also be made with other macerated fruits.

Paula's Crème de Haricots de Maïs

Creamy Bean Soup with Croutons and Crispy Ventrèche

Serves 4 to 6

1 pound dried Tarbais beans

1 carrot, cut into ¼ inch dice

1 large onion, cut into ¼ inch dice

4 tablespoons duck fat

Salt and freshly ground pepper

1 cup diced crustless dense country bread

3 ounces lean ventrèches, pancetta, jambon de Bayonne, or Serrano ham, slivered (about ½ cup)

2 tablespoons minced fresh chives

1 cup heavy cream

Pinches of piment d’Espelette

1/ Pick over the beans and soak them in water to cover by at least 2 inches for 12 hours.

2/ The following day, rinse and drain the beans and set aside. Meanwhile, in a heavy 4 to 5-quart flameproof pot, preferably earthenware, gently cook the carrots and onions in 2 tablespoons of the duck fat, stirring, until tender, 5 to 10 minutes. Scoop out and reserve about ¼ cup of the onions and carrots. Add the drained beans and 2 quarts fresh water to the pot. Bring to a boil, reduce the heat to moderately low, add a pinch of salt and pepper, and simmer for 2 hours, or until the beans are tender and the liquid is reduced.

3/ In a medium skillet, heat the remaining duck fat. Add the diced bread, slivered ventrèche, and the reserved carrots and onions. Fry, stirring, until crisp. Remove to a side dish, add the chives, and set aside.

4/ Let the beans cook slightly, scoop out about 1/3 for garnish and set aside. Press batches of the remaining beans and liquid through the fine blade of a food mill or puree in a food processor or blender. Add the bean puree to the soup. Stir in the cream; bring to a boil and simmer for 5 minutes. Correct the seasoning with salt, pepper, and red pepper to taste.

5/ To serve, divide the reserved beans among soup bowls, ladle the hot soup over the beans, and garnish each portion with a spoonful mixture of fried onion and ventrèche mixture. Serve at once.

Joie de Vivre carries Tarbais beans, duck fat, Espelette pepper, and ventrèche.