What happens when trains don’t run? Major inconvenience. France is slowly emerging from one of its longest strikes. Spearheaded by RATP and SNCF rail workers, this national grève had its biggest impact on banlieusards, those who live on the outskirts of Paris but commute to work in the capital. I used to be one of them; let me assure you I’m not one bit nostalgic about those times.

Gare de Gourdon at dusk

In our little corner of La France Profonde –where public transportation is minimal– this strike mostly affected high school and college students who rely on train service to reach their schools in Brive, Cahors, and Toulouse. At times, the Gourdon train station was completely deserted as traffic between Paris and Toulouse came to a standstill. But what happens when trains stop running for good? What happens to the stations, the grade crossing keepers’ houses, the bridges, the rail beds?

Gourdon then…

The historical importance of train service can’t be overstated. In the US, whole cities grew up as rail centers, especially west of the Mississippi: Rick’s hometown Modesto was founded in October 1870 with the coming of the railroad. In France and in the rest of Europe, where towns and villages had developed over the course of centuries, the establishment of a train stop was a highly anticipated and celebrated event: it favored economic growth, regional and national commerce, and population migrations. It also provided a lot of jobs.

Gourdon now

Our train station in Gourdon was inaugurated in 1891 and life changed overnight: it would now take only 15 hours to reach Paris, instead of the 14 days (!!!) required by horse-drawn coaches. The station is four kilometers from our house and sits on the Paris Austerlitz to Toulouse line: nowadays the trip takes about 5 hours. Although we can’t get TGV service on this line, I treasure the convenience of reaching the center of Paris in a comfortable Intercités, without transferring to another train. For the past decade, frequency has declined and there are rumors of SNCF wanting to cancel the stop at our station, thus forcing us to transfer in Brive. Locally, nobody likes the idea and demonstrations regularly take place in town and at the station. Sometimes, les manifestants gather on the rails for a picnic.

Payrignac then…

Payrignac now

Today, I’m taking you along a local rail line that disappeared… and experienced a second life. At the tail end of the 19th century, a young man from the Aveyron came over here to work on a brand-new junction between Gourdon and Sarlat. While working in the area, he met and married a young woman who lived in Payrignac. After the line opened in 1902, he moved back to Espalion with his bride, my great-aunt.

The lampisterie in Payrignac: the small building next to the station was used to store light bulbs and portable lamps.

Restrooms behind the lampisterie.

My grandfather worked as a trackman on that line before moving to Paris where he continued to work for the Chemins de Fer d’Orléans. During school breaks, Dad and his siblings took the train for free to return to the family farm. Catching their train at Austerlitz, they would get off in Gourdon and transfer to reach Payrignac, the first stop on the Gourdon-Sarlat line. Their grandfather would meet them at the station and load the suitcases in his wheelbarrow. After a short 250-yard walk, they were home.

The old schedule

The line was single-track with one train and there were three roundtrips per day. It took about 40 minutes to cover the 10 miles separating the two towns. Sarlat was not a tourist destination yet but a main hub for commerce. Agricultural products like tobacco and walnuts were handled and transformed in local plants: my great-aunt rode the train to Sarlat to sell her load of shelled walnuts to a wholesaler. Shelling walnuts at home, à la veillée, was a way for women to chat with family or neighbors during the long winter evenings and bring in extra income.

There are still many railroad bridges on that stretch of RD 704

Things changed dramatically in 1937 when the SNCF was created to merge and operate all French rail companies. The Gourdon-Sarlat line stopped transporting passengers in 1938 and freight traffic ceased two years later. Most of the rails were pulled from the tracks and melted down to be used for weapons in WWII. From that point on, Dad and co. had to schlep their luggage from Gourdon to Payrignac on foot, a long hilly four-kilometer walk.

Saint-Cirq-Madelon then…

Saint-Cirq-Madelon now

The line was decommissioned in 1955 and SNCF subsequently started selling off the buildings along the way. The Payrignac, Saint-Cirq-Madelon, and Groléjac stations were purchased and transformed into private homes.

Mobile barrier at Saint-Cirq-Madelon

Original ties at Saint-Cirq-Madelon

I followed the line and stopped at all the old stations to take pictures and sometimes talk with their owners.

Payrignac was a cute fixer upper

The Payrignac station was fixed up many years ago and serves as a second home.

Vintage signal at Saint-Cirq-Madelon

More vintage equipment

The man who originally bought the Saint-Cirq-Madelon location still uses it as a second home. He has kept old signage and equipment as “décor” in his yard around the building.

Groléjac then

Groléjac now

The Groléjac station is now a workshop for a chaisier.

La Voie Verte: bike and foot path around Groléjac

Trains used to cross the river at Groléjac; now bikes and hikers use the same bridge.

The Dordogne département had a good idea and purchased all SNCF properties along the line. After removing the leftover tracks, they turned the rail bed between Groléjac and Sarlat into a piste cyclable that is used by hikers and cyclists.

The railroad bridge of Groléjac crosses the Dordogne river

Picture-perfect hamlet framed by an old bridge

A remarkable stone bridge crosses the Dordogne north of Groléjac. Smaller bridges arch over a scenic stretch of Route Départementale 704.

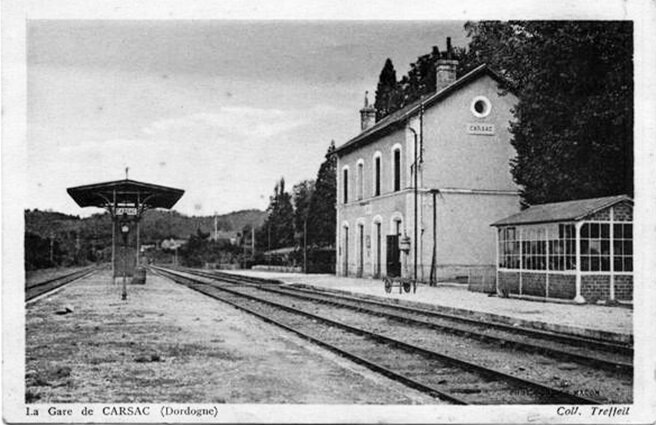

Carsac then…

Carsac now, with the bike path

The old Carsac station was turned into a primary school. It was the last stop before Sarlat.

Sarlat then…

Sarlat now

The Sarlat station is still in use. Bordeaux can be reached via regional train service (TER) in about 2 hours and 15 minutes.

These old signs seem to illustrate the competition between road and rail. Guess who won that battle…

It’s not difficult to know what the future holds for our remaining “local” stations in rural France. Most folks own cars nowadays but trains are vital for students and the elderly who rely on them to reach schools or medical specialists in larger cities. With privatization on the horizon, the trend in France is to favor regional hubs, especially those served by high-speed trains, and abandon smaller markets. Large train stations are being transformed into shopping malls; smaller ones may well become endangered species. Perhaps I should join the demonstrators in Gourdon and bring cheese and saucisson to the picnic…

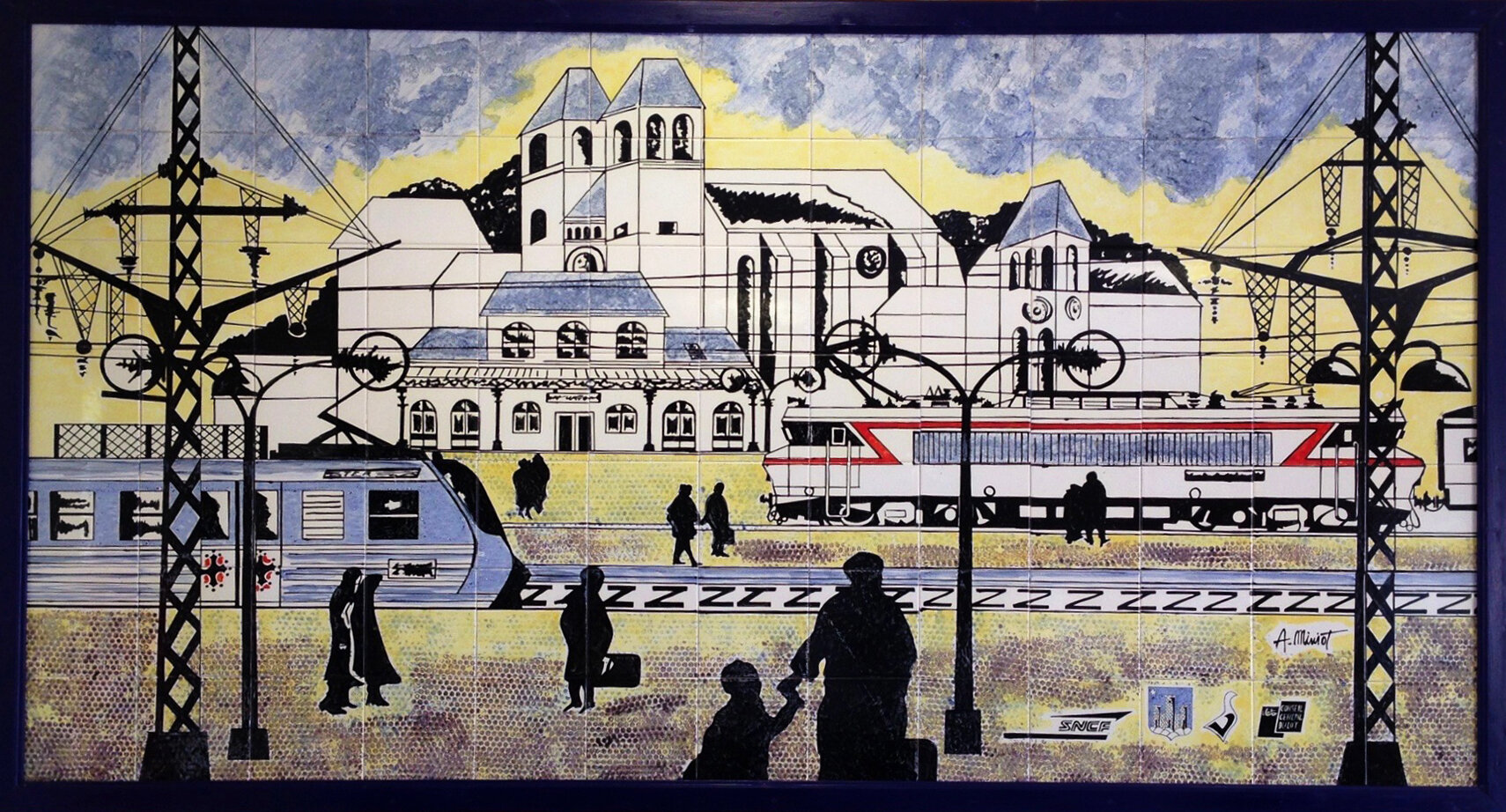

Inside the gare de Gourdon, ceramic tiles tell the story

Vocabulary

La grève: strike

Le banlieusard: someone who lives in the suburbs

La France Profonde: lit. deep France; out in the country (way out…)

Le TGV: high-speed train (Très Grande Vitesse)

L’Intercités: (m) classic train between major cities

Le manifestant: demonstrator

La veillée: after dinner hours in the countryside, usually devoted to conversations between family members and/or neighbors that also included “productive” activities (knitting, mending clothes, shelling walnuts, etc.)

Le chaisier: someone who makes and restore old chairs

Le département: county

La piste cyclable: bicycle path

La route départementale: a road maintained by the département (county)

Le TER: Train Express Regional; a regional train that is not so “express” since it stops at many stations…